Glitch!

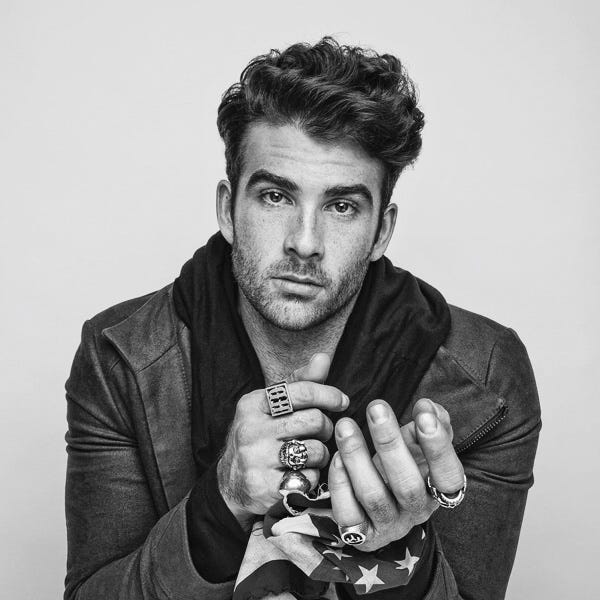

The Eternal Story of Hasan Piker

In a past life, somewhere in the distant multiverse of the 15th century, Hasan Piker is a Catholic clergyman soldier calling upon his forces to crusade against the Turks and follow the one true religion.

He is not the online influencer of modernity born and raised in Turkey and now championing Hamas in its war against Israel from a gaming chair in Los Angeles.

He is, at a different time altogether, a poet in the 19th century — maybe Rudyard Kipling himself — encouraging the American empire to colonize the Philippines in the aftermath of the Spanish-American war.

To support his imperial mission, he sends a letter to his troops:

“Take up the White Man’s Burden

Send forth the best ye breed—

Go bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives' need;

To wait in heavy harness

On fluttered folk and wild—

Your new-caught, sullen peoples,

Half devil and half child.”

Although today, Hasan promotes videos of islamists screaming at the top of their lungs that infidels must be defeated, in another part of the multiverse, he appears as the opposite incarnation, as a military man profusely praying to the God of the Christians to descend upon Jerusalem and rain hell fire upon the Muslims.

In his 2025 manifestation, Hasan is militantly anti-Zionist.

But elsewhere, in the multiverse, he is not.

I have met him in many lifetimes and in many forms. So have you.

He is the son of Nike, goddess of Victory. But he remains unaware of his father, the mad Jester, who will use him to cross-pollinate the world.

I hope that introduction was as riveting as I want it to be.

The truth is I only just learned about Hasan Piker a few days ago in this article in The Free Press. Before then, I’d never even heard of him.

As I recently mentioned in another post, I’ve been binging the work of the poet and philosopher Bayo Akomolafe whose understanding of the world is sideways and backwards and messy but also beautiful and true.

Very simply, it reveals how the politics of victory is its own ideology and how disorientation, failure, and defeat can shape us in miraculous ways and crack us open to new ways of knowing.

This archetype playing itself out in the cracks, in unexpected crevices, and which defies our yearning for victory can be called Trickster or Mad Jester Energy.

According to Tarot, the Trickster or Fool symbolizes the “cosmic Life Breath” and “is propelled forward by impulse and cathartic creation.”1

Trickster is an energy that exceeds our ontologies of reduction and our itch to categorize everything along the lines of good-evil, oppressor-oppressed, sinner-saint.

Today, most of our politics follows this narrow linearity. “Positionality” — or the animating principle that my position must defeat your position — rules Washington and the metaverse.

Many men in particular flock to Twitter or Twitch or the Joe Rogan podcast to demonstrate how pure and righteous they are in their positions all the while remaining totally oblivious of how this is their way of making ritual and sacrifice to Nike, the Greek goddess of Victory, who is everywhere in the culture, in our hearts and on our tennis shoes, and who has been communing with our civilization for a long, long time.

But Nike has a secret. Her consort is Trickster. Wherever she goes, there he is, moving through us beyond our conscious awareness.

In order to acquaint ourselves with him, we must learn to walk upside down, and practice our headstands and move roundabout, like capoieristas or pigeons teaching their flock to fly.

To know Trickster, we must enter sideways through backdoors and alleyways so that we might catch a glimpse of the ambiguous, illegible Mystery alive in all things.

If we stretch ourselves in these ways, we might begin to notice that although in our politics we often desire victory over our enemies, in defeating our enemies, we will inevitably be shaped by them.

This is the inherently creolizing nature of evolution mocking our politics of purity and toying and making love with the goddess of Victory.

Think of this the next time you hear of Israel vs Palestine, regardless of what side you’re on.

In this war, taking the shape of your enemy is unavoidable.

If you define yourself as pro-Israel, you are shaped, inescapably by Palestinians. And if you define yourself as pro-Palestine, you are shaped, inescapably by Israelis.

If one side succeeded in wiping their mortal enemy from the face of the earth, they would find that their nemesis was still inside of them, still lingering, still shaping them, reconfiguring them, and choreographing the epigene that determines how they move about in the world.

I’m thinking now of the anti-normalization politics that many who consider themselves pro-Palestine take up in the BDS movement. The idea behind anti-normalization is that if you consider yourself pro-Palestine, you shouldn’t engage with Israelis unless they are anti-Zionist and share your political views.

Hasan Piker certainly feels this way. He’s stated that if you have any warm feelings toward Israelis, you shouldn’t be allowed to be a dog catcher, let alone be welcome in normal society. According to Hasan, banishment and exile is the only humane response to structures of apartheid in Israel.

But anti-normalization is a form of apartheid. It is the attempted refusal to encounter the other and the assumption that you can know the other without encountering them. It is the rejection of immanence and the assumption that so long as the other does not share your perspective, this alone makes them fully legible, graspable, and knowable.

Built into anti-normalization is the very architecture of the Israeli occupation: a structure marked by hyper-surveillance and control built to mitigate the fear that encountering the other might lead to physical and spiritual contamination.

All of this is ironic. There is something violent and extractive about the idea that Hasan could know someone before encountering them that feeds into the very paradigm he is telling his fans to avoid.

As Akomolafe points out, “our people are always yet to come.”

I highlight this not to demonstrate that Hasan is evil or that the Israeli government is evil but that the 16th century colonial project of purity permeates us and that Hasan is imbricated, enmeshed, and incarcerated in the colonial architecture he seeks to destroy. He cannot annihilate Israelis or zionists or puritans or colonialists or white people without annihilating himself.

Neither can you.

The earth is not that neat.

It is not convenient, it is not tidy and it is not pure.

It neither progresses nor conserves. It does not move along the linear grid lines we craft to pretend otherwise.

The earth protrudes and spills over and we emerge only through this process. We are changed by what we wrestle with and we cannot help but wrestle — with other humans, with North American wind patterns, with the lichen growing under the boulders that form our highways and with the very act of sitting down to write on Substack.

The earth does not revolve around us because it is us. We belong to it and, being its creatures, we must contend with the reality that it is ultimately unknowable, ungraspable, and un-conquerable — just like our enemies are, and just as we are. There is no overcoming of this because we cannot overcome the very territory that makes us possible.

It is this disorienting glitch embedded in the fabric of reality that I use to study Hasan Piker, not to portray him as a hero or a villain but as a bit character in a play orchestrated by forces beyond his control: Forces like Nike, the goddess of Victory which morphs and moves us, and alchemizes ontologies of light and dark into meta-narratives that enlist our fleshly bodies to worship at her altar, just as the poppy plant enlisted British bodies to clandestinely trade opium to the Chinese and plunge the country into addiction in the 19th century.

This de-centering of the human voice in the larger story we tell ourselves is the glitch; it is the shuffle-step-shuffle-step between Jester and Nike. It is the invitation that might crack us open and help us find new ways of relating to the sorrows of our era.

I’m feeling that sorrow now as I write.

Given my personal and abiding friendship with Am Yisrael, Sorrow wells in me, astounded that I would refrain from villainizing Hasan.

But I am trying to unearth the 16th century puritan preacher who has terraformed the territory I inhabit and who is accustomed to swimming in only one stream of water, seeing only one frame, and serving only one mission — that of achieving victory over the heathens. I am trying to get him to see how much the heathens have shaped him.

I am also not saying that if you pass judgement or damn Hasan that you’re wrong. You can pass judgement all you want. It doesn’t really matter. My exploration isn’t hierarchically situated: I am not saying that my analysis is better than yours.

I am simply sidestepping the question of what’s “better” in the first place and exploring, more for myself than anyone else, the illegible ways that Nike, goddess of Victory, dances with the Mad Jester and how this dance presupposes us, embeds itself in us, and makes a fool out of all our orthodoxies.

So, let us dance.

In Octavia Butler’s book Parable of the Sower, Lauren Olamina must navigate the end of the world.

After being violently displaced from her home, she must find safer ground in a foreign land which is especially difficult because she is an empath who can literally feel the pain of others.

This extra sense means she must take great care to avert her eyes on the road when passing strangers who are being violently assaulted or afflicted with disease. It also means that it will always be risky for her to harm others — even when she must do so to protect herself — because any time she inflicts pain on others she will feel it acutely in her own body.

So, when the time comes, Olamina must kill swiftly and decisively or else she will feel a paralyzing pain that incapacitates her. It is critical that her enemies be spared from suffering. In this way, war creates intimacy and Olamina’s foes come to shape her own being.

Although Parable of the Sower is a fiction, this fundamental entanglement is true of all our relations. In fact, it is what makes us possible.

The beautiful North African tradition of Mimouna, a Maghrebi Jewish custom that marks the end of Passover with sweet leavened bread and mofletta and Arab Muslim hospitality would not exist without exile or displacement. Mimouna is a spillage borne out of disarray and violence and enmeshment with the other. It bears the mark of entanglement.

No matter who, in the heat of our political passions, we seek to conquer, the very act of conquering will transform us. In this way, the goddess of Victory and Jester are always dancing.

As I heard someone say in a podcast recently, it is not, as Audre Lorde once put it, that the master’s tools cannot be used to dismantle the master’s house but rather that the master’s tools do not stay the master’s for long.

Take, for example, how in the article on Hasan, Josh Code writes that Hasan repeatedly calls Israelis and zionists “inbred.”

That intrigued me so I went to the New Oxford American Dictionary to look up the meaning of the word.

One entry stuck out to me and revealed a glitch. It reads,

“bred from closely related people, especially over many generations.”

The glitch here is that the rhetoric Hasan uses to condemn Zionism is itself closely related to the colonial epistemologies he seeks to destroy, and his entire persona — the ripped, hot, man with the proper socialist instincts driven by an intense fitness regimen — is itself bred from industrialized modernity which has been churning since the invention of the steam engine.

Hasan’s posture, like so many today, reinforces the mechanized, sterile politics of purification, the same one that sent European empires scrambling to convert the natives in Africa and rescue them from their backward, animistic ways. So even Hasan’s foreign policy positions are inbred, formed from closely related people, over many generations.

Hence when he calls zionists inbred, it is a verbal tool of contempt and ridicule and mockery that falls back onto itself. It does not remain the master’s tool for long.

“Defeat the masses of infidels!”

This was the cry that Houthi Islamists in Yemen chanted on a video Hasan endorsed and shared to his 30,000 followers last September.

But again, that word — “infidel” — is just another word for inbred, or impure, or sinner.

It is a synonym for the monstrous, dark, messy, unenlightened figure who must be sacrificed by the religion of progress and who must be conquered so that believers in the true religion — whatever that is, it changes depending on who you’re talking to and in what century, geography, and climate you happen to find yourself in — can obtain a smooth, perfect, painless, spotless, state of transcendence.

“Defeat the masses of infidels” is not a climate-neutral slogan. It is a battle cry to escape the dirty soiled earth and the messy entanglement that comes with being its seed.

In Seeing Like A State, James Scott writes that this “ideology of high modernism is best conceived as a strong, one might even say muscle-bound version of the beliefs in scientific and technical progress that were associated with industrialization in Western Europe and in North America.”2

And in Everybody’s Protest Novel, James Baldwin observed that liberal humanists who preached easy gospels with the promise of equality and salvation that could be obtained simply by having the right politics were actually corrupt.3

He wrote,

We have…in this most mechanical and interlocking of civilizations, attempted to lop this creature, [the human being], down to the status of a time-saving invention.

In over looking, denying, evading his complexity — which is nothing more than the disquieting complexity of ourselves —-we are diminished and we perish;

only within this web of ambiguity, paradox, this hunger, danger, darkness, can we find at once ourselves and the power that will free us from ourselves.

It is this power of revelation which is the business of the novelist, this journey toward a more vast reality which must take precedence over all other claims.

What is today parroted as his Responsibility — which seems to mean that he must make formal declaration that he is involved in, and affected by, the lives of other people and to say something improving about this somewhat self evident fact-is, when he believes it, his corruption and our loss;

moreover, it is rooted in, interlocked with and intensifies this same mechanization.

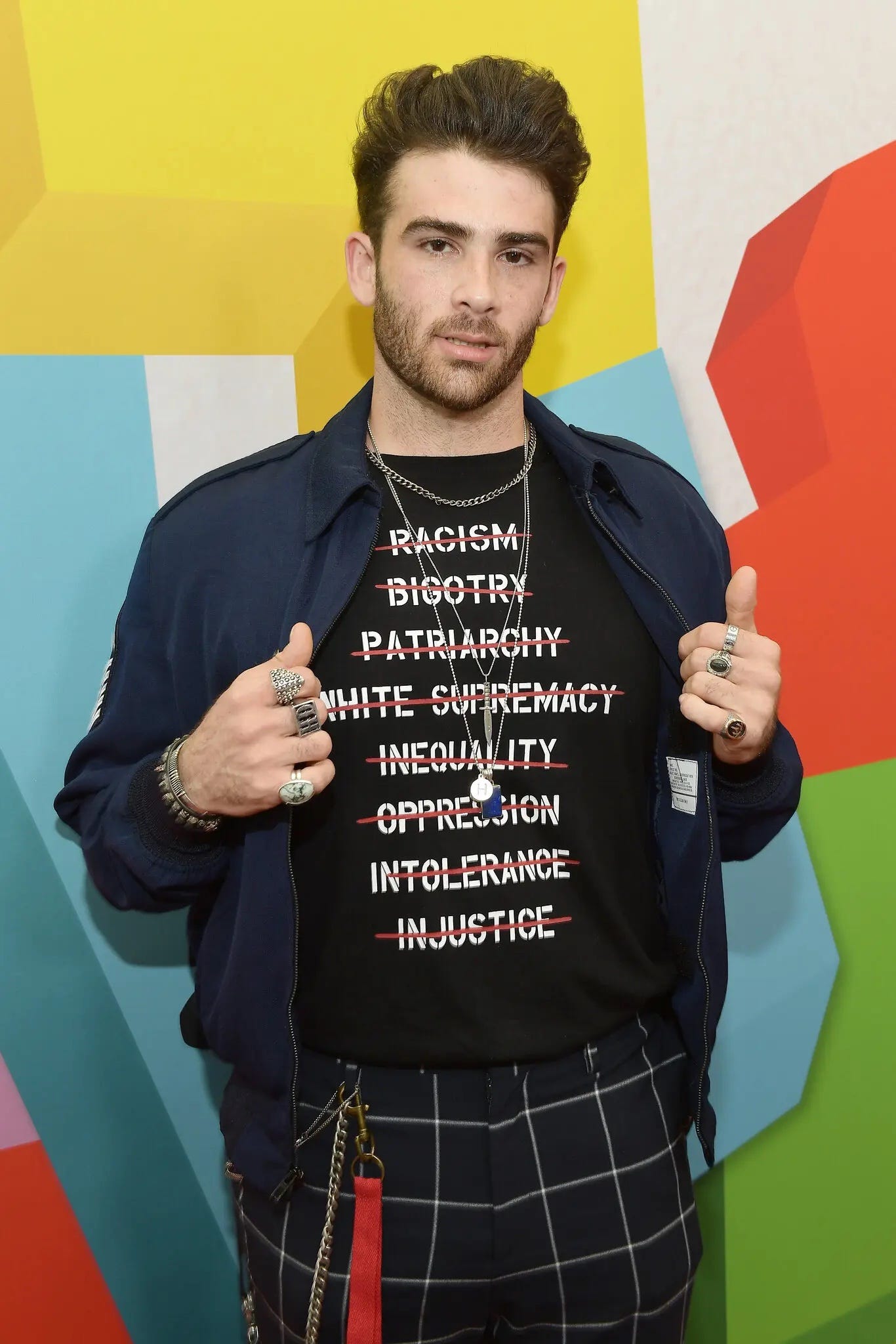

Maybe reread that quote one more time, slowly, and then look at the shirt Hasan is wearing in the picture below:

How easy! How utterly Responsible of him!

That Hasan’s “bro” persona has attracted millions isn’t that surprising. We’re attracted because we’ve been entrained in this gospel for centuries, both prior to and since the days of the industrial revolution.

We love the neatness of it, of having the right, clean, and proper politics that will distinguish us from the dirty backward hordes who are weak, feckless sinners.

What, after all, is the material difference between the battlecry to “Defeat the masses of infidels” and to “Take up the white man’s burden”?

One has borne the other.

Whiteness, in the simplest most basic understanding of the word, is pre-racial. It’s an ontology that seeks to do away with stains, with cracks, with anything considered dirty or soiled or messy, like, oh, I don’t know, an actual human being.

So, having been weaned on the cult of progress, on the belief that “the past is a ‘valley of darkness' out of which humanity is emerging into the light,”4 why wouldn’t we croon over Hasan who efficiently ingests his meals with “precisely 1.1 pounds of roasted chicken breast” every day and who wears t-shirts that make neat proclamations that say “injustice is bad”?

None of this is to define Hasan as a villain. Again, this is not a guilt trip. I do not exist outside of the paradigms I critique. I am shaped by them too. I also want to defeat the infidels, though when I say that I mean the jihadists.

But I’m a musician and I cannot escape the fact that it was only when the Berber Muslim Almoravid dynasty took over the Maghreb region of North Africa in the 1050s and declared jihad against Christian Europe and forced thousands of black Sudanese men into slavery to serve as their soldiers, that the heathen backward animist African drum made contact in Spain for the first time and transformed European music for the better, forever.5

This is the crack in purity politics. It is the Jester making love to Nike. The wild always gets through because the wild is what we fundamentally are.

Does this thesis frustrate you at all?

Are you upset that I, like the earth, refuse to come to a solid conclusion about who is right and who is wrong here?

Is it disorienting to know that the animist forces of Victory and Jester enlist your body to do its bidding, whether you like it or not?

What do you do when you are disoriented, when you no longer know up from down?

You learn to play Capoiera.

You stand upside down and reorient.

You fall to the ground and notice how your life is not your own and that it exceeds its own boundaries.

Notice how you are a constellation of microbial bacterium and errant heat waves and an assemblage of ancestors, some of whom were rapists and murderers and thieves, and, if you go back far enough, definitely inbred.

Notice how a non-trivial amount of how you operate and move about in the world comes pre-coordinated.

Learn to discern that things can only be read through each other, not in isolation, and everything is a mutual web of relationships and nothing and no one is merely clean or pure or just.

Hasan Piker is not only indebted to the colonialist systems he seeks to dismantle. He is a carrier of those systems. Maybe this means he is evil but, more interestingly to me, it means he is monstrous.

It means he is not the neat, isolated linearity he thinks he is.

His grooming schedule notwithstanding, Hasan has been bred by closely related people over many generations.

And so have you.

So the next time you feel tempted to engage in positionality politics, or to think that the only thing that matters is defeating your enemy, the next time you are inspired to chant, “Together we will win!” maybe rethink that. You probably won’t and even if you do, it’ll only be temporary.

But you will dance.

That’s how the glitch comes in.

Thanks for reading! For just $5 a month, you can support my work. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber today!

Hundley, Jessica. The Library of Esoterica. Taschen, 2020.

Scott, James, C. Seeing Like A State. Yale University Press, 1998.

Baldwin, James. Everybody’s Protest Novel. Beacon Press, 1949.

Lasch, Christopher. The True and Only Heaven: Progress and Its Critics. W.W. Norton & Company, 1991.

Sublette, Ned. Cuba and its Music. Chicago Review Press, 2004.

"Whiteness, in the simplest most basic understanding of the word, is pre-racial. It’s an ontology that seeks to do away with stains, with cracks, with anything considered dirty or soiled or messy, like, oh, I don’t know, an actual human being."

Feels like most of the hate in the world today is latent shame. We think destroying our projections will free us of whatever parts we avoid at all costs. Are we externalizing internal battles as a form of escapism and writing it off as righteous activism?