“So far, incredible as it may be, no Negro-leader seems to have made any extensive political use of the so-called survival techniques and idiomatic equipment for living that the blues tradition has partly evolved in response to slavery and oppression.

Even more incredible is the fact that most Negro leaders, spokesmen, and social technicians seem singularly unaware of the possibility of doing so. There are many spokesmen whose fear of being stigmatized as primitive is so hysterical that they reject out of hand any suggestion that U.S. Negro life style is geared to dance-beat improvisation.”

-Albert Murray, The Omni-Americans: Some Alternatives to the Folklore of White Supremacy

Theory.

Back in 2020 I had this creeping suspicion that Ibram X. Kendi did not know how to dance.

I fantasized about debating the popular historian whose simplistic idea of “how to be an anti-racist” struck me as square and joyless, a sentimental, bleak, and destitute painting of American life.

Kendi’s book seemed to be everybody’s protest novel from 2020-2022. Like the blood of the lamb placed above the houses of the children of Israel during Passover, ‘How to be an Anti-Racist’ was the pamphlet everyone put on their shelves to prove they were good people and not worthy of the eternal damnation the Angel of Death would so righteously enact on America for its original sin of racism.

I’ve written at length about my intellectual disagreements with Kendi, so I’ll try not to belabor that point. But the fantasy of a dance-off with him lay in my deep and furious sense that Kendi perceived humans as soldiers in a battle, with one side fighting under the banner of “racism” and the other under “antiracism.”

As was written in the New York Times back in June 2024, “Kendi argues that history is not an arc bending toward justice but a war of “dueling” forces — racist and antiracist — that each escalate their response when the other advances.”

There’s something maddeningly cruel and reductive about this vision. It erases the “power, poison, pain, and joy,” of the human being; and if we cannot begin to look for answers to the problems we humans face from a place that honors the messy sacredness of the human being, what’s the point of all of this conversation about ending racism anyway?

I’ve been in a long and fitful relationship with melancholy all my life. So the idea that history is a never-ending war of Armageddon that will go on until the sun turns black strikes me as ruthlessly nihilistic. And, as the drum-beat improvisational style present in all African spirituality, it is also ahistorical.

I’ve been reading a really beautiful book called “Cuba and its Music: From the First Drums to the Mambo” by Ned Sublette. The writer points out how the confluence of cultures that were produced by slavery, colonialism, and racism also produced not just incredible music but all the music we know and love. The music of African slaves completely transformed 16th century Europe.

How?

Sublette writes how “the polyrhythms of African traditions slowly infiltrated Spanish and Portuguese musical forms, laying the groundwork for what would later become a global rhythmic revolution."

African slaves not only survived but also profoundly influenced the cultures they were thrust into, reshaping music, dance, and spirituality in Europe before creating the foundation for the vibrant musical traditions of the Americas.

There are many gems in the book that expound on this point. Here’s a particularly fascinating one, an astounding observation on the indelible impact of the Congo on all the music you’ve ever listened to:

“The modern history of the Congo is one of unparalleled disaster. Rich in natural resources (‘raw materials’, in industrial parlance,) it went from being a mass-producer of slaves for transatlantic traders, to a provider of slaves for trans-Saharan traders (who came to the Congo late), to a slave-labor fiefdom of Belgium’s King Leopold II…

Yet that same Congo with its deep culture of magic, music, and dance, must be reckoned one of the most important influences on the way we do things in the modern world. We know some of those influences. But beyond what we can explicitly identify, there are other things beneath the surface that lurk in disguise or in some less formal memory. There are cultural echoes, things we don’t have the tools, the science, or possibly the will to investigate just yet…

The culture of the Bantu-speaking peoples is the great overlay, the common element whose omnipresence links the African music cultures of the New World, from deep blues to samba, and links all the parts of Cuba to each other. Every slave port in the Americas received Bantu slaves at one time or another. The Bantu, enslaved in the greatest numbers are the common element throughout the African New World. Angolans built Brazil, period. In Haiti, vodou is a mix of Dahomeyan with Congo tradition. Bantu came to Jamaica, Trinidad, and Puerto Rico. In New Orleans, there’s Congo Square. All over the southern United States, you find traces of Congo culture. Funky, says Robert Farris Thompson, is a Congo concept, the word deriving from the Kikongo lu-fuki, meaning ‘strong body order.’

Much of the sway of the world’s popular music today comes one way or another from this large zone of Africa, as a musical lingua franca so basic that hardly anyone ever stops to think: Why is this our rhythm? Why are these the moves we like to do? Where do they come from? We may never be able to answer the questions fully, but we do know that a lot of it comes from the Congo, and a lot of it comes from the Congo via Cuba.”

Hence violence and brutality are not the only outputs of history. There is also resilience, music, song, and dance — and this matters more if we want to teach our children how to make it through dark times.

If there be any ideological war then, it is not between racists and antiracists but between those who can see this and illuminate it for others and those who do not, and who instead view history as a cynical Hobbesian nightmare in which the state must pass constitutional amendments appointing panels of “racism experts” with the ability to discipline public officials for racist ideas.

Life is a joyous, musical dance, punctuated as all great music is, with high notes and low notes, with sorrow and happiness, with melancholy and rapturous ecstasy. The trouble with all this is that such an experience cannot be so easily recorded in what we call “data.” It is of a different category entirely.

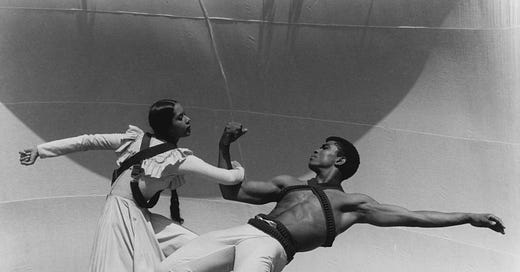

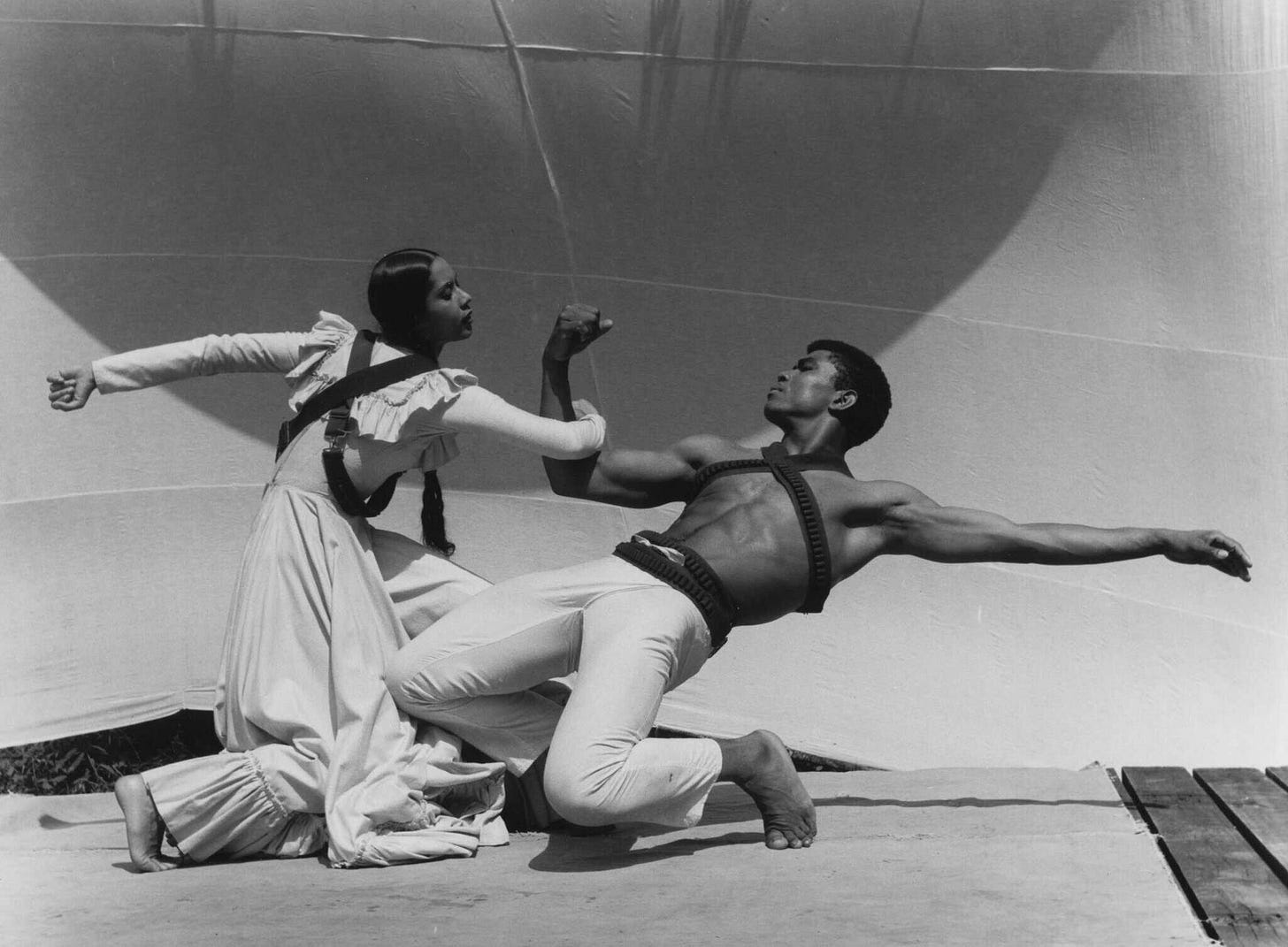

And so my fantasy remains: I’d love to challenge Ibram X. Kendi to something that defies reductive binaries. I would not be interested in trying to impress the audience with fancy rhetoric or in proving my intellectual chops but, after all bouts of exasperation have passed, I will simply want to dance.

Dance transcends all. It is not an argument. It is a different kind of provocation altogether, one that edges us into awe. And it is ultimately awe that gives rise to grace, that potent life force in human beings that equips us with the capacity to treat each other well, and the proper-view that forms the basis of all just social policy.

So, I’d choose a gracious, poly-rhythmic song in the genre of Afrohouse or Afrobeats to dance to.

This is a genre I know well since I heard it in my mother’s womb.

I have the dance-beat algorithm in my veins. It was bequeathed to me eons ago by my ancestors and early on in my own lifetime through number-clapping games I played with my sisters and double dutch competitions I watched in elementary school. I know this in my bones and I cannot explain this to you scientifically.

Now obviously I have no idea if Dr. Kendi can dance. I read that he chose the name “Kendi” as a last name because it means ‘loved one’ in Meru, a fact that suggests he does know how to tap into the poetics that make all living things come into being. I wish he would have written with that sensibility in his book.

I also know it must have been a toll for someone so introverted and soft-spoken to be catapulted into the public eye and to have millions of people project a “savior complex” onto him, especially while battling stage 4 colon cancer. I feel great compassion for him and sense that his conclusions derive from a dispirited place;

which is precisely why in any debate with him, the proper thing to do would be to dance.

Practice.

The other day I was at a jam session with some friends and felt jealousy creep in my insides. My friend was playing guitar and singing. He excels at both. I have long wished for the ability to excel at one or the other but am mediocre in comparison. And so, as he played, I felt jealousy.

I’ve done a great deal of somatic work and I know what jealousy feels like in my body; it takes me out of the present moment and puts me in a state of stuck-ness. A great tell is that I become foggy and oblivious to the beauty in my peers and my environment. I sang the romantic pop songs, one after the other, but I was judging my singing harshly which meant it didn’t come out as good as it could’ve.

I’ve been doing somatic body healing work for long enough to know that these complexes appear in me as cycles. They are not linear. They rise and then they fall.

But as they rise, it feels as if they will stay forever and then I become desperate to escape this feeling. Guilt accompanies jealousy which just compounds it and ensures it’ll stay longer. Any feeling that is resisted persists. This is one of the rules of the infinite game.

I wanted to grab some ketamine to take me out of the fog but I’m taking a break from K at the moment. So my own restrictions forced me to settle into some of the somatic practices I’d been working through for the past 5 moons. (I like replacing the word months with moons since thats what the word means.)

I looked within and searched.

“What are you trying to teach me” I asked my jealousy. '“Come and stay awhile. Sit, and let’s have some tea.”

Almost immediately, the answer became clear:

“If you are feeling jealous, then sing the songs as if from the perspective of a jealous lover.”

Suddenly, I shifted.

I began to sing with the instructions I received from within and the feeling of stuck-ness dissolved. It was as if the instructions were as follows:

“Place your jealousy into the song itself. Listen to the lyrics deeply as if they were written by a jealous lover. Act it out in your singing as if you’re at the theater. This way your jealousy will have some place to go.”

After I did this, the fog melted and I saw my friend in all his beauty. I softened my gaze and became present.

And I realized that I had reached for ketamine the moment I sought to escape. (That’s sort of what ketamine does.) This was a beautiful revelation since it taught me the nature of my relationship to the substance and it taught me that I could have an active relationship with my emotions, the very substance and life force of my being.

SOMA.

// “Tanzania” by Uncle Waffles, Tony Duardo, Boibizza, and Sino Msolo //

Thanks for reading my latest piece! In February, I’ll be coaching 16 individuals in a six-week cohort that focuses on deep somatic work; we’ll learn how to track our vagus nerves, get curious about what’s happening in our nervous systems when we go into threat responses (like fight or flight), and learn interoception - the ability to sense and be aware of what's happening inside our bodies, including our physical and emotional states. If you’d like to join you can sign up for the waitlist here!