In X-Men First Class, a young Charles Xavier makes a crucial mistake when attempting to train Erik Lehnsherr to channel his rage. By using his telepathic powers to “read” Lehnsherr’s emotions, Xavier is able to see his rage, anger, sadness, and also “the brightest corner of [his] memory system". He tells Lehnsherr, who, as a Holocaust survivor witnessed a Nazi murder his mother, that he sees “not just pain and anger” in him but “good, too.”

That “too” was Xavier’s mistake and, for all of his genius, it reveals a remarkably immature relationship with what depth psychologist Carl Jung called “the feeling function” in a human being. Xavier’s suggestion that emotions like anger and rage are inherently bad, morally inferior feelings that should be tucked away and surpressed made Lehnsherr’s transformation into an evil arch villain practically inevitable.

The author and poet Robert Bly wrote about this inevitably in his book ‘A Little Book on the Human Shadow’; (and my bookclub is studying this text right now; If you’d like to join us this week, grab your tickets here!)

Bly writes:

“The drama is this. We came as infants ‘trailing clouds of glory,’ arriving from the farthest reaches of the universe, bringing with us appetites well preserved from our mammal inheritance, spontaneities wonderfully preserved from our 150,000 years of life — in short, with our 360-degree radiance — and we offered this gift to our parents. They didn’t want it. They wanted a nice girl or a nice boy……[and yet] when we put a part of ourselves in the bag, it regresses. It de-evolves toward barbarism…

Every part of our personality that we do not love will become to hostile to us.”

This is precisely what happens in X-Men First Class.

Lehnsherr is effectively Xavier’s shadow, a term which means the parts a person cannot see and accept in themselves. Xavier is not able to accept the darker feelings that mankind possesses, and certainly not his own. He labels these as “bad,” projects the "badness” onto Lehnsherr and tries to convince him to suppress them. “We have it in us to be the better man,” he says. But being “better” means that Lehnsherr must put anger in a bag and deny the full range of his emotion.

This Lehnsherr cannot do.

And naturally, in the end, Lehnsherr revolts and becomes hostile to Xavier. He rejects his way of seeing things and becomes Magneto, Xavier’s arch nemesis and lifelong enemy.

Curiously, Xavier also becomes paralyzed when he fights with Lehnsherr. This is appropriate and a fittingly poetic end for a man who becomes cut off from his own dynamism and life force when he fails to give anger and rage their due.

What could have happened had Lehnsherr been given a dojo to play with and channel his rage and anger appropriately, without stigmatizing those emotions as “bad”? Plenty of cultures have built ritualized containers to assist in the appropriate channeling of these basic human emotions.

The burning of effigies; drum circles; wrestling; role playing: These are just some examples of containers that have been used in many cultures, eras, and across diverse geographies to help communities channel their collective anger into a vessel that can hold it and transmute it. It is through these vessels that humans have been able to fully feel their feelings.

If we don’t fully feel our feelings, there can be no transformation, and without transformation, our suffering becomes meaningless.

This meaningless is unbearable so we escape through repression, disassociation and other defensive mechanisms which, once transformed into habit, become addiction. As Buddhist psychiatrist Mark Epstein wrote, all addiction is a longing for the transcendent in distorted form.

Unfortunately in the United States, this distortion is our norm. Our culture remains very comfortably — and unconsciously — rooted in the 16th century Calvinist doctrine of repression. This is a doctrine whose adherents perceived human emotion, including exuberance, enthusiasm and joy, as inherently sinful. Loud singing and dancing even in church was a no-no. Any cheerfulness needed to be tempered with fear.

Puritan doctrine perceived humanity as inherently evil and as such, remained unable to consciously relate to it. Naturally, this repression occasionally became too hot to hand and Puritan society had to project their repressed fears and anxieties through periodic outbursts onto those perceived to be morally inferior, like women. You’ve probably heard of the most famous Puritan exorcism: The Salem Witch Trials of 1692.

All of this is part of our cultural inheritance. These doctrines are the primordial waters we swim in. As sociologist Max Weber pointed out, it is this puritanical “Protestant Ethic” that is the foundation of how we relate to each other and of capitalism itself.

And, for me, this is the most relevant context through which we ought to be examining our feelings toward Luigi Mangione and the murder of Brian Thompson, the CEO of United Healthcare.

I am sincerely grateful to my Puritan forefathers and mothers for making it through persecution, disease, and all the other countless tribulations they had to overcome to build society. I do not deny their spiritual gifts and talent for industriousness.

But I don’t wish to claim the emotional repression they took up as spiritual doctrine as my own. It is not mine.

I seek instead to a live a life of radical honesty and truth.

So here goes:

When I heard that Brian Thompson, the CEO of United Healthcare was murdered, I felt nothing.

What do you call that? Indifference? Apathy? A lack of concern?

Let’s go with those.

Maybe this was because I had just spent two months watching my best friend spend weeks in the hospital with a plethora of doctors who failed to successfully diagnose her autoimmune disorder, who gave her conflicting information about the best next steps to take, and who remain mired in a system mediated by insurance providers who saddled her with debt.

I hadn’t spent so much time in the hospital before this Fall. I assumed, pretty stupidly, that being in the ER was actually like that show ER from the early 90s.

Newsflash: it isn’t.

Instead I got my most intimate, upfront look at the chaos, and, most surprisingly, the prison-like feeling of being in a hospital for more than 24 hours. I would never wish it on anyone.

As days passed, I started to feel a combination of emotions in response to Thompson’s murder. I looked up his profile and saw that he was a husband and father. I felt heartbroken for his children. I read that last year he suggested a shift in his company’s strategy to a focus of “value-based care” for customers and felt confusion, a tragic sense of what could have been, and a mildly cynical feeling of distrust, like I didn’t actually believe him.

I read about the lawsuits he’d been embroiled in, the AI algorithim used under his tenure to deny coverage to patients, including, according to the New Yorker, a man in Tennessee who broke his back, was hospitalized for six days, and who was then told his coverage would be cut off two days after. After trying and failing to appeal, he left the nursing home and died four days later.

United HealthCare also denied a middle-school-aged girl long term residential treatment. She was struggling with suicide. She eventually succumbed. These are not anecdotes. United Health Care has a higher-than-average rate of coverage denial. The company also schemed, allegedly, to inflate its stock; and it violated antitrust laws, a breach for which it was investigated by the Justice Department in 2024.

All of this is fundamentally unjust and morally bankrupt.

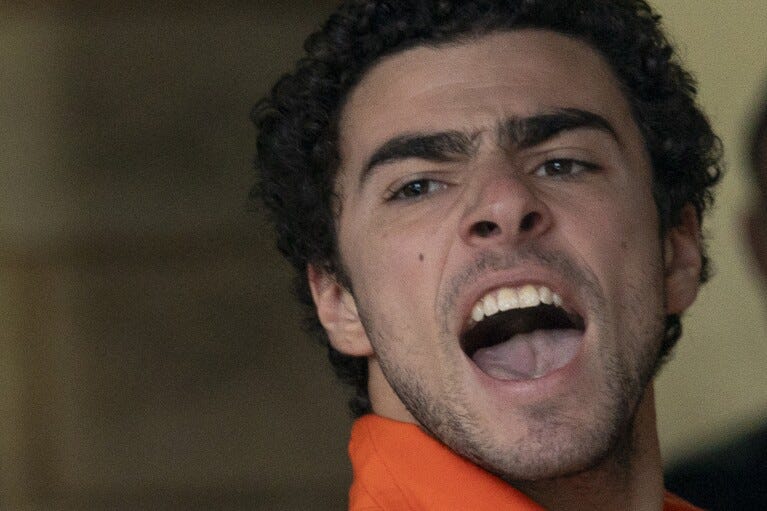

And so I watched the memes and jokes that celebrated the killer, Luigi Mangione, poured in on instagram and I felt…comforted. Some of the takes were pretty clever and certainly great fodder for a comedy set. And I felt furious at the online takes that trafficked in self-righteous moralizing and claimed the glee was “un-American.”

To the contrary: the glee is nothing more than a symptom of our health care system, a reflection of the callous, indecent, cold-blooded way we treat each other. If it is un-American then by that logic, United Healthcare’s behavior is also “un-American.”

Are my feelings wrong? If I feel these feelings, am I a bad person?

This question is — and I mean this sincerely — a stupid question, a relic of our Puritan heritage and beside the point.

Feelings are neither good nor bad. They are a complex interplay between neural circuits, hormonal signaling, and the body's physical state in response to external stimuli. They arise automatically, outside of our conscious control and we have some options in terms of how we relate to them.

Option A is to do so unconsciously. This is the mode American society is currently mired in. We are ashamed of, deny, and repress our feelings because feelings come from the body and we perceive our bodies as repellant, grotesque, and deformed.

Deep down in our Calvinist bones we view the human body as innately dirty and in desperate need of salvation, and salvation can only be achieved in our secular times by making as much profit as one can. This is not an exaggeration.

Here is Weber articulating the connection in ‘The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism’:

“Asceticism looked with a positive and favorable eye upon the acquisition of money, but as an end to the subjugation of the flesh and human desires…[emphasis: mine] The earning of money within the modern economic order is... considered an end in itself. This is so familiar to us that its significance is not easily appreciated. It is, however, not at all self-evident... it is a result of the Calvinist ethos.”

The Puritan belief in predestination motivated the community to look for worldly signs as proof of God’s deliverance in the world to come. Success in business was one such sign and a strong one at that. The contemporary practice of humans valuing profits over people is not mere happenstance. It is logical behavior borne out of an ascetic worldview fashioned for us centuries ago.

There is a deep current of self-hatred here and it is obviously unsustainable.

Eventually, this repression becomes too much like a valve that’s clogged and ready to explode, so we discharge our emotions explosively, sometimes by murdering a CEO or gleefully posting our support of the deed on instagram.

This is the primordial soup out of which our healthcare system has risen. It is the spil that produced Luigi and the collective’s response to Luigi, both the sneers and the cheers. To critique it without criticizing the system at play is like giving a patient medicine to manage her pain without creating the conditions for them to heal.

The alternative to all of this is for us to heal by painstakingly learning how to relate to our feelings consciously. This is an act of maturity. It requires building ritualized containers in community so we can channel our darker, more baser instincts.

And again, just to clarify, by “baser,” I mean “human” instincts that are ancient and primal, and therefore indispensable qualities of our life force. This is, in my mind the new frontier of healthcare, and discovering any new territory will come with pitfalls and monsoons. We should move delicately but swiftly.

One of my favorite teachers once said that it is only when we validate all our feelings that we have more choices available to us in terms of how we can respond to whatever is arising.

A great way to visualize this is to notice how when you repress, your body contracts. There is a palpable hypertension you are storing and it takes a lot of energy to keep this up. Imagine a society where you no longer had to store unnecessary tension in your body. Imagine you could responding to the present moment as a porous, open, clear-headed being, unafraid of whether or not you were saved or facing eternal damnation.

This would be a very different society.

“My sadness is indistinguishable from a certain heaviness of my bodily limbs… my delight is only artificially separable from the widening of my eyes, from the bounce in my step and the heightened sensitivity of my skin…Meaning..remains rooted in the sensory life of the body — it cannot be completely cut off from the soil of direct, perceptual experience without withering and dying.”

- David Abram, Spell of the Sensuous

Validation of feelings doesn’t necessarily mean acting them out to the fullest extent. The power of ritualized containers is that they equip communities with the means to act out their feelings without hurting others.

But more deeply, validation of feelings means recognizing and honoring the sacred ephemera of your body which is ancient and a carrier of a great deal wisdom. It learning to respect and track your nervous system by doing deep somatic work. And it means giving up the old Calvinist attitude of self-loathing.

This piece is my tiny-yet-mighty attempt to do that and to relate to my feelings consciously. I invite you to do the same. Maybe if enough of us commit to this work, we can build a better healthcare system for all of us. This is my great hope.

May it come to pass in our lifetimes.

Beautiful and thoughtful piece. I don't know if I understand all of the implications, but it's given me a new way to think about how we relate to our emotions. Have you heard Shalom Auslander talk about the concept of "Feh"? He had a great interview on Yascha Mounk's podcast. It sounds like you two are on a similar wavelength in identifying the harms of collective self-loathing.