Soil of my Soil

Bone of my Bone

Blood of my Blood

I bless you

Aṣẹ

~ Annie, Sinners

Spoiler Alerts Below

I have always been a dancer. Somehow, I acquired this ability in my mother’s womb. Dance is my first language. Rhythm terraformed me before I was born.

When I sense the beat, I am brought back to the ancestral plane. I can’t really explain this in words. But when I move, I can feel my West African ancestors moving through me and others who witness this, I’ve been told, can feel them too.

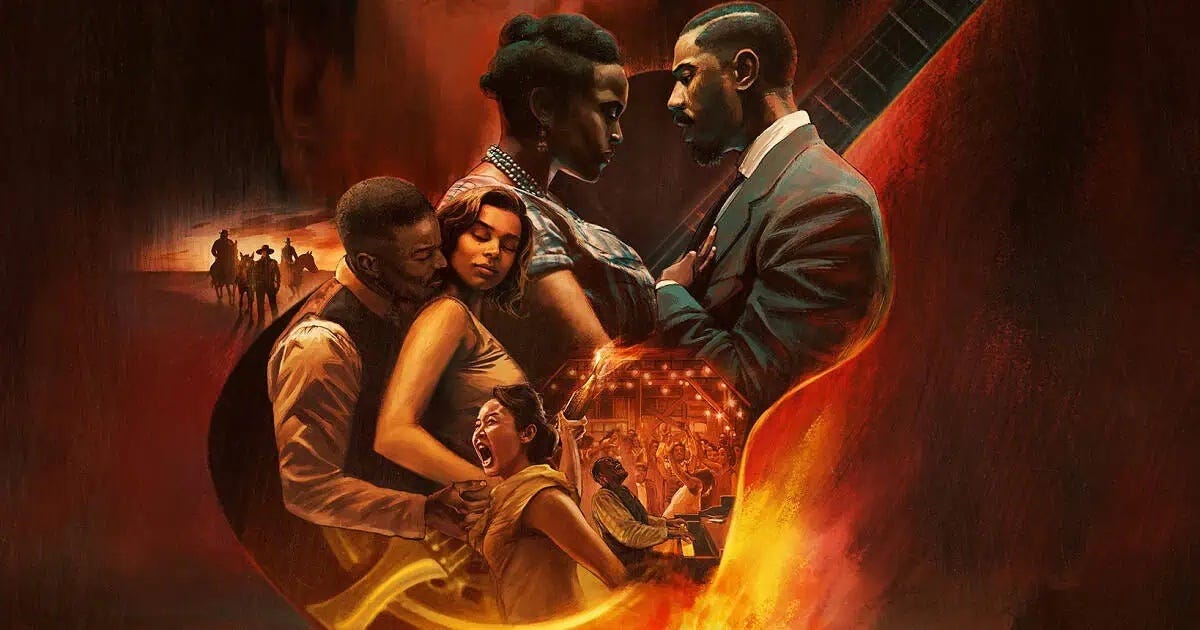

So when I watched Ryan Coogler and Michael B. Jordan’s Blockbuster new film Sinners, I felt seen.

Set in Clarksdale Mississippi in the 1930s, Sinners is a film filled with many questions and murmurings that stir my soul: the spiritual power of music and the way it brings forth the Muse; Christianity and its… complicated relationship to the polytheistic animistic traditions it colonized and assimilated; how the grammar of both these traditions wrestle inside me and in all of us as we are all composites; and how racism creates restless hungry ghosts who find no solace on this plane and feed off others in futile search for rest.

If you haven’t seen it yet, go run to the theater. I’ve seen it twice now and wouldn’t mind seeing it a third time.

Here’s a little more on the plot.

Twin brothers (brilliantly played by Jordan) return from Chicago to establish a juke joint and make some money. These twins are gangsters; they left for Chicago 7 years prior looking for refuge from the South but found Jim Crow in the North disguised as sky scrapers. They acquired some money working for Al Capone and by playing Irish and Italian gangs against each other. But ultimately, they don’t find what they’re looking for and decide to return to their hometown to deal with the devil they do know.

Their business plan is simple. Set up a club, get amazing musicians (like Preacherboy Sammy, an incredible blues guitarist and singer), keep the drinks flowing, and eventually, profits will be made.

There’s only one problem. Preacherboy Sammy is an incredible artist who doesn’t fully understand his power.

He has the gift of the muse.

His playing is so good that it pierces the veil between the living and the dead. When he plays, Zaouli dancers from the Ivory Coast come out from the past and crip walkers from a California that has yet to exist emerge too. As his friend and root worker Annie explains at the beginning of the film, “There are legends of people, with the gift of making music so true it can conjure spirits from the past and the future. This music can bring healing…but it can also attract evil.”

That evil comes in the form of vampires — specifically, people who used to be white but who, once dead, become blood-sucking zombies who wander through the American south playing Irish jigs in search of the old ways of Dublin. Of course, they’re not actually able to find their way back home, so they murder everyone along the way in order to grow their vampire tribe. And when they hear Sammie playing, they become entranced because they recognize he has the power to conjure up the spirit of their ancestors.

This is brilliant storytelling. It’s anthropological, political, and ecological in its framing all at once, and a dancing nerd like me can’t help but geek out on the openings and entanglements this film reveals about the human condition.

Before being bitten, Remnick, Joan, and Bert are white. Hell, Joan and Bert are card carrying members of the klan.

But after they’re bitten, they revert to being Irish. They remember the old ways — and the old music — of their ancestors who were marginalized when they first came to America.

In other words, being bitten by a vampire de-racializes you, which is, if you stop and think about it, a conservative’s wet dream. Color blind America anyone?

Once you become a vampire, you yearn with your long-lost countrymen and you’re initiated into a cult of hungry ghosts who roam about longing for a universal brotherhood of vampires of all races who can live together in equality forever.

This film throws shade at both the right and the left. Its subtle lesson, I think, is that such solutions to racism are a little too easy.

“We was never gon’ be free,“ says Stack to his twin brother Smoke after being bitten.

He argues that they should all become vampires so they no longer have to deal with being underwater as businessmen or live the gangster life or deal with Jim Crow.

According to vampire gospel, salvation from the troubles of this world can only be found through conversion, not in the world of the living. Living is too much. After all, it includes the Klan. Being undead forever is presented as a form of redemption.

But what’s so damn curious about this message (in addition to its low-key shade against all political orthodoxies) is that the invitation to be bitten is not foreign. It contains the architecture of Christian doxology. It is an evangelical offering. Fellowship and love are guaranteed if you join; Heaven on earth too, as well as the promise for folks to be together forever.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Musings with Chloé Valdary to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.