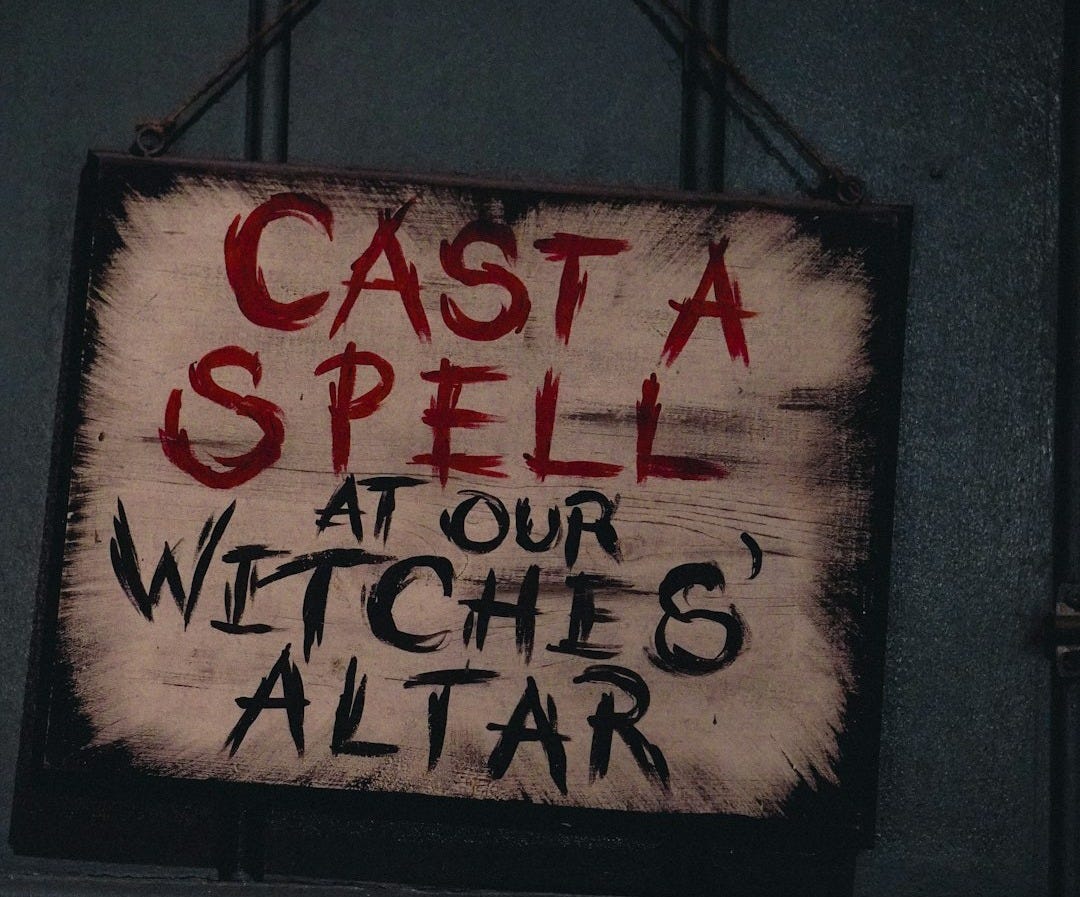

There are two New Orleans’s(ss, lol). There’s the one you’re probably familiar with or have maybe heard about: The witchy, voodoo super-Catholic-yet-also-super-pagan New Orleans famous for grave sites with burial grounds above the earth. This is the New Orleans that, if you are a tourist, probably feels like a perpetual Dia de los Muertos festival, the most superstitious place in all of America, and certainly the most esoterically spiritual.

There’s also New Orleans’s famous cuisine: its seafood, gumbo and other gulf-sourced delicacies.

There are the oak trees which you cannot help but look at and think, “Ohhhhh, it’s Magic!”

There’s the willowing wisps that give the city an otherworldly feel, as if you’re in an enchanted forest even though you’re actually just out on Canal street. All of this combined with the improv lifestyle of a city whose motto is “Laissez les bons temps rouler,” (or, “Let the good times roll”) makes New Orleans a truly magical place, like no other on earth.

And then there’s the New Orleans I grew up in, or, at least the one thrust upon me in my adolescence; and that New Orleans was very very different.

I grew up in a New Orleans that was on guard against itself, a conservative protestant New Orleans that rejected Mardi Gras and saw it as a form of evil; a New Orleans that disdained the eating of shellfish since the book of Leviticus prohibited it; a New Orleans which, far from being a purveyor of magic, was instead designed to be a protective amulet against such things.

There were times in the recent past where I looked back on these aspects of my upbringing — aspects I used to adore — and felt resentment; but as an adult I’ve come to see a glaring through line between both these versions of New Orleans that turns their contradictions into complements; and that through line is both triumphant and heartbreaking.

You see, New Orleans is dying and has been for a long time. And these two responses seem to me to be two very different attempts to honor that dying.

New Orleans is essentially underwater; she is a bowl that can barely keep Lake Pontchartrain, the Mississippi, or the Gulf of Mexico out of her midst, and every hurricane season she and her inhabitants are reminded of their inescapably temporary fate.

Perhaps so many Nola natives want to let the good times roll because the good times are finite, fleeting, and will likely one day come to an end. This is, deep down, probably the same reason why my parents fought so hard in their own way to keep the darkness of death away from their children’s watchful eye. All of this is to affirm life.

There is a great deal of uncanny, inexplicable, weird magic in New Orleans and it really is spooky. There is also lawlessness, crime, and corruption. My upbringing was a warding off of that too. And sometimes when I zoom out, I can’t help but think that so these responses are naturally occurring phenomenon emerging in a landscape that is on its death bed and making its way sometimes maddeningly, often ebulliently, through the 7 stages of grief.

There is, after all, a good chance that New Orleans will one day be an island floating in the Gulf of Mexico. There is an equally good chance it will simply disappear. And if you were born and raised in New Orleans like me, you could not escape this fact.

You boarded up your home every year in preparation for its inevitability. Come Hurricane season every August you made sure you stocked up on batteries for flash lights, canned goods and bottled water. You watched the weather forecast like your life depended on it because it did. And when the electricity went out, you turned on your radio, you listened and you prayed.

If you teach your children to memorize bible verses, know the 23rd psalm by heart, and be sure to be in church every Saturday (not Sunday, because in my house, the Old Testament is King), you’re not just practicing devout Christianity. You’re boarding your house up in a place where dry land is not guaranteed, in a place where water has an archetypal, larger-than-life meaning, and has the power to swallow you whole.

So there is no such thing as an atheist in New Orleans; there are only those who respond to death by painting murals of skeletons, holding festivals in honor of death, and celebrating it, and those who try to ward it off through the teaching of religious literacy, thou shalts and thou shalt nots. Both are spells of different forms. And both are part of my heritage. And all my recent visits to New Orleans have been an attempt to reconcile the two by being grateful that both these spells — or, ways of seeing — stir within me.

I have been visiting home for Thanksgiving ever since I moved away nearly ten years ago. Each visit has been a kind of pilgrimage, a deepening of my self-knowing, a homecoming in more ways than one. And every year that I return, I grow more conscious.

The first few years that I visited, I remember going into disassociation. I was easily triggered by nearly anything my parents would say, especially my mom, since I am so very much like her. (They say this is how it always is, hehe.)

Also, back then, I was on birth control and my cycle never came…until I would go home to New Orleans. It was as if some strange internal clock would start ticking whenever I touched down in my homeland. I was tired all the time and, when visiting my parents house, I would often fall asleep on the couch and stay asleep for hours.

Some Jungian analysts have much to say about this phenomenon of falling asleep when visiting the ancestral plane. In their writings sleep is a sign both of psychic lethargy and transformation on the horizon and that idea really resonates with me.

Looking back, I feel I fell asleep because my old self was dying and I needed to commune with my unconscious for spiritual renewal. Those early visits were a liminal stage for me, like the caterpillar entering the cocoon before her transformation into a butterfly.

I remember one particular year where I felt my parents’ orthodoxies no longer served me and I found myself growing resentful; but I read a book by Rabbi David Wolpe called ‘David the Divided Heart,’ and it brought me great calm.

In this book, King David, the famous king of the ancient Israelites is revealed in all his many facets to be not just one single thing but a container of multitudes. He is a king, a lover, a Fugitive, a sinner, and a father. He is also a dancer, a musician, and a warmonger. He is all of these things in one.

The book brought me respite because it was the first text I’d read that pointed out how multifaceted and complex David was — and it gave me the permission to own my own complexities. It was as if by reading that book I was being seen. I realize now the role that book has played in helping me accept New Orleans in all of her many facets as well.

In the last few years I’ve developed a very strong (and daily) spiritual practice that has helped me stay in the present moment whenever I’m home. It is my own amulet that I’ve fashioned for myself; my practice helps me ground and remain true to my personal relationship with the Divine which is inspired by but looks very different from my parents’ traditions. (I’ve written about this before here. I’ve also since picked up some new spiritual practices, including a daily chanting practice I received from the great Maryn Azoff.)

As a result, the last few years visiting New Orleans have been a dream — or, better yet, closer to reality. Before, I’d been viewing New Orleans through my parents’ eyes or through the eyes of a juvenile who was attempting to rebel against her parents but never simply on her own terms, with an acceptance of what her parents believed but also a conscious decision to choose to walk her own path. I’m grateful to say the mist has cleared. I’m standing in full acceptance of all of my heritages.

This year I danced on Frenchman St. and downed my first daiquiri in the French Quarter. It was great. There was a really funky bass player at Snug Harbor whose musical vibes stirred my soul. Ten out of ten, would recommend.

The night I danced on Frenchman St, something else stirred within me.

I tried to sleep but couldn’t because my right arm spasmed for hours. I never experienced anything like this and, in perfect New Orleans fashion, I immediately became superstitious.

So weird.

Was this because I was trying to celebrate the city on its own terms, much to my heavenly Father’s chagrin?

Or was it the opposite, some kind of evidence that all the parts of me were finally integrating and my twitching arm the proof in the pudding?

OR was it just because I had that extra cup of coffee earlier that afternoon?

I don’t know I’ve had two cups of coffee in a single day before and that didn’t made my arm twitch for hours.

I tossed and turned that night. Turned the lights on, then back off again. I tried talking out loud to myself and tried singing myself to sleep.

My thoughts made sense of the spasm first by descending into self-contempt. (This is a thing I do. My fight-or-flight reflexes sometimes manifest as self-hating ruminations.) Then I started praying in the traditional fashion.

Then, in the wee hours of the morning, near 5:30 am, my thoughts shifted into acceptance. I started to think of all the new truths I’d recently learned to hold about myself. I said them to myself matter-of-factly, without needing to prove my self worth one way or another.

I don’t know if it was that or that the spasm simply wore itself out, but it was around that time that it stopped. I’d like to believe that it was the acceptance that did it. They say that once you accept a thing, it changes. It’s a little bit like that rule in quantum physics, the one that says the if you pay attention to a phenomenon, the phenomenon changes form.

So much of our culture is addicted to proving things, instead of making its peace with the unknown. Sometimes I wonder if this has been true since the dawn of the Enlightenment. But true attention is not in service of anything; it cannot be in service of proving something one way or another. True attention reveals the mystery inherent in all beings and reveals the truth that we are all constantly changing forms, dying to our former selves, and being reborn and renewed by the waters of life.

This is the great education I have received from New Orleans, my beloved hometown, and I am so grateful for her teachings. Visiting her will always be a pilgrimage, a dharmic trip to wonderland, and to the depths of my soul.

I thought we called that second New Orleans Metairie?

I should’ve known you were from New Orleans (maybe I did and forgot, I’m capable of any kind of mental error); I am too, and live there again; and I credit much of my good fortune intellectually and spiritually to it. I don’t think I’d have found ways through our century as readily otherwise.